In the ancient Benin Kingdom, spirituality was never separate from governance, war, art, or daily life. What many outsiders call “voodoo” was, and still is, a structured belief system rooted in ancestor worship, deities known as “Orhionsa,” and the sacred authority of the Oba. These spiritual practices are not fringe or hidden. They are embedded into the very architecture of Edo culture, from the coral-beaded rituals of coronations to the offerings made at ancestral shrines.

The Edo people believe in a layered universe. At the center is Osanobua, the supreme creator, who granted humans free will and assigned each person a destiny. Supporting this cosmic balance are various spirits and deified ancestors, many of whom are invoked through rituals that involve chants, masquerades, and sacrifices. This structure formed the basis of the Benin royal court’s spiritual legitimacy.

Royal Rituals and the Power of Isekhure

One of the most important spiritual offices in traditional Benin is that of the Isekhure, a high priest who serves as the Oba’s spiritual adviser and link to the ancestors. The Isekhure performs purification rites for the king, the palace, and the land. These ceremonies are believed to maintain harmony between the human world and the ancestral plane.

Contrary to sensationalized portrayals, these rituals are not acts of sorcery. They are complex spiritual traditions meant to heal, protect, and maintain societal order. For example, the annual Igue Festival is one of the most important royal spiritual events. It involves the Oba blessing the land and his people, while also receiving spiritual renewal himself. During this time, specific rites are performed to cleanse the palace and strengthen the kingdom’s fortune for the year ahead.

Symbolism and Legacy

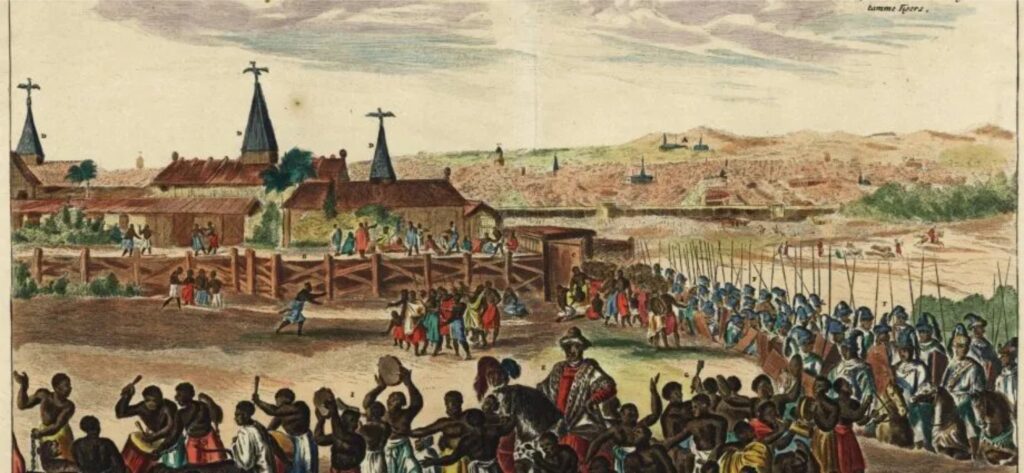

Edo spirituality is rich with symbols. The leopard represents royal power. The coral beads signify purity and ancestral authority. Charms, known as “ukhurhe” and “ebo,” are used for protection, fertility, and justice. Many of the Benin Bronzes, now displayed in museums around the world, depict spiritual scenes, gods, and royal rituals. These objects are not mere art pieces. They are vessels of sacred memory and religious significance.

The influence of these practices continues today. Many Edo families maintain private altars where they make offerings and communicate with their forebears. Traditional priests are still consulted in times of crisis. Even among modernized communities, there remains a deep respect for the spiritual systems that shaped Benin’s identity for centuries.

References

- Nigerian Tribune – Understanding the Spiritual Power of the Benin Kingdom

https://tribuneonlineng.com/the-spiritual-power-of-the-benin-kingdom - The Guardian Nigeria – Benin’s Ancient Spiritual Legacy

https://guardian.ng/life/the-spiritual-legacy-of-benin-kingdom - World History Encyclopedia – Religion in the Kingdom of Benin

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2070/religion-in-the-kingdom-of-benin