You can hear it in the bata drums echoing through the courtyard at dawn. You can feel it in the thunder of horses galloping during the Durbar. You can see it in the calculated steps of dancers moving in harmony at an Igbo festival. These rhythms and rituals carry the memory of generations. They are not just traditions; they are declarations that we belong to something greater than ourselves.

Aisha, from Katsina, speaks of her Fulani heritage with gentle pride. Her grandmother’s proverbs, spoken in Fulfulde, are soft but sharp with wisdom. There is a quiet elegance in their lifestyle, a sense of order and grace that shapes the way they speak, live, and host. Aisha says that hospitality is not just a gesture in her culture. It is an art, a value passed down like heirlooms.

In Enugu, Emeka finds his pride in Igbo customs. For him, it is the connection to ancestors, the strength of family names, and the rituals that honor the dead. He describes the New Yam Festival as a celebration that binds the living to the past. Every libation poured and every name spoken carries weight. It is not simply about remembrance. It is about gratitude.

Symbols That Speak Without Words

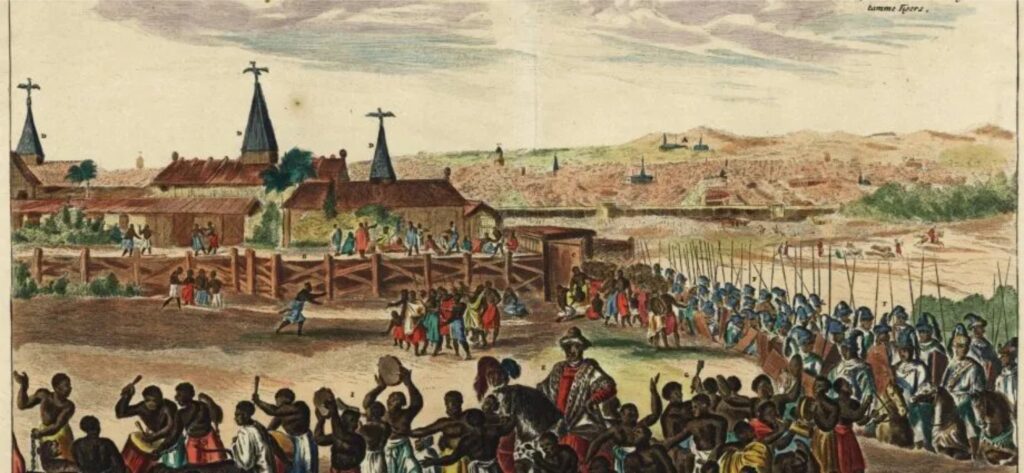

Cultural pride often wears a visible face. From the bronze plaques of Benin to the intricate coral beads of the Itsekiri, Nigerian cultures express their identity through symbols. These are not just ornaments. They are silent storytellers. They speak of lineage, struggle, craftsmanship, and pride.

Ireti, a textile artist from Ondo, talks about Adire with reverence. Each piece of cloth holds a story. Turtles, stars, and eyes etched in indigo represent messages that words cannot capture. When she wears her grandmother’s dyed fabric, she does not just wear fashion. She wears history.

Hair, jewelry, and body markings also carry meaning. For many, these choices are more than aesthetic. They are cultural codes, worn in public to say, “This is who I am. This is where I come from.”

Culture That Breathes

What makes Nigerian culture powerful is its ability to evolve without losing its soul. In Lagos, young professionals wear native outfits to meetings. In Abuja, Tiv girls teach their classmates greetings in their mother tongue. In Port Harcourt, Kalabari boys blend masquerade dances with contemporary beats.

Tunde, a designer based in Surulere, insists that you do not need to live in the village to carry your culture. On Fridays, he wears agbada to work. He plays fuji music on his commute. He signs his emails with his oriki. His culture is not a memory. It is part of his rhythm.

For many Nigerians, culture is not just something to remember. It is something to live. And that is where pride begins.

Reference:

- Culture and Identity in Nigeria: A Living Heritage — African Studies Review (cambridge.org)