Every morning in Kano, the Emir’s palace opens its doors to a steady flow of visitors. Traders come with disputes, students seek scholarships, and elders bring petitions. There is no official title for what the Emir does in those moments, and no government salary attached to them. Still, in many ways, his presence alone carries real power. He is not a lawmaker, but his word holds weight. He is not elected, yet he represents something enduring, an authority rooted in the people, not politics.

In other parts of the country, similar scenes unfold. In Benin City, a young man recalls how the Oba’s involvement helped resolve a long-standing land dispute. In Oyo, residents gather outside the Alaafin’s compound before planting season to observe a traditional rite. It is a spiritual practice no local council can enforce, yet one that the community honors deeply.

Stories like these unfold quietly, every day. For many, they prove that Nigeria’s monarchs are more than symbolic figures. They remain essential parts of their communities, woven into the daily and spiritual fabric of society.

A Country in Conflict With Itself

Despite their cultural significance, doubts persist about the place of royalty in today’s Nigeria.

In a country grappling with insecurity, poverty, and political distrust, some citizens question whether monarchs are still relevant. Critics point to the lack of accountability, the hereditary nature of royal positions, and their sometimes extravagant lifestyles. Some argue that these rulers have become ceremonial placeholders, more spectacle than substance.

Still, even these criticisms acknowledge a deeper truth. Nigeria’s democratic system has not replaced the need for cultural stability. In places where government presence is weak or ineffective, traditional rulers step in. They settle disputes, maintain order, and offer spiritual guidance. Their role is not official, but it is trusted. They are not above the law, but they often remain when formal institutions fail.

Through the Eyes of the People

“I don’t know if the king in my village has any real power,” says Chika, a 26-year-old medical student from Anambra. “But when my uncle died, it was the Igwe who showed up. He helped resolve our family issues. He knew how to speak to everyone, young, old, even the stubborn ones. Nobody else could have managed that.”

For Musa, a tailor in Sokoto, the Sultan is more than a ceremonial figure. “When trouble comes, we listen to him before the politicians. His words carry peace.”

Not everyone shares that sentiment. “Some of these kings only appear during festivals,” says Ifeoma, a content creator in Lagos. “They live large and seem out of touch with the people. It’s hard to relate to someone who doesn’t understand the everyday struggle.”

Still, whether praised or criticized, traditional rulers are not forgotten. They occupy a unique space in the Nigerian consciousness, one that no elected official can fully replace.

Culture Is Not a Costume

Being a monarch in Nigeria is not just about wearing a crown or holding court in a palace. It represents identity, lineage, and cultural memory. With more than 250 ethnic groups across the country, each royal figure stands as a guardian of language, customs, and history.

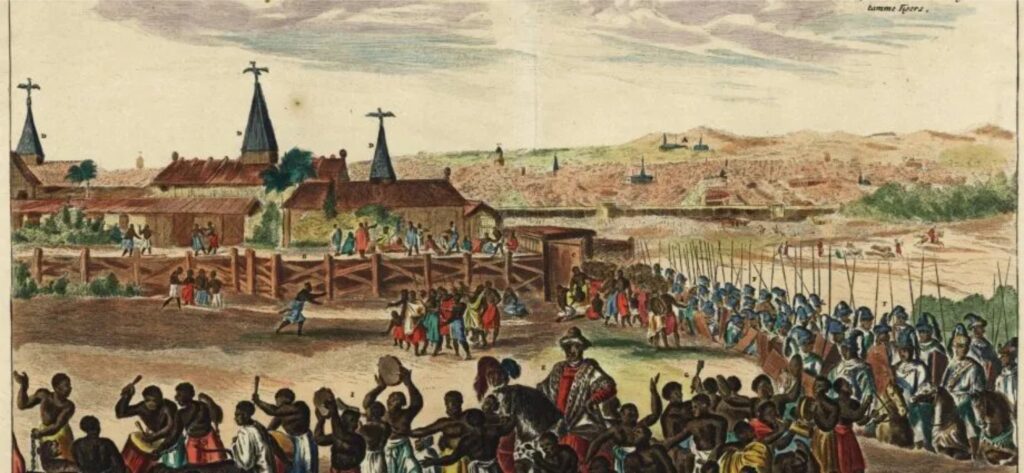

When a king participates in a durbar, leads a yam festival, or presides over a naming ceremony, he is doing more than performing a ritual. He is protecting something sacred. These ceremonies are reminders of where people come from, and why it matters.

To many Nigerians, the relevance of royalty lies not in governing power, but in cultural grounding. Kings and queens offer a sense of continuity in a country that often feels unstable. They give people a reason to be proud of their heritage, even when the future feels uncertain.

So… Do They Matter?

Yes, they do, although in a different way than they once did.

Today’s monarchs may not make laws or control armies, but they continue to shape how Nigerians view themselves. They preserve identity, offer moral guidance, and provide cultural leadership when official systems fall short. In a country as diverse and complex as Nigeria, that role is not just symbolic, it is essential.

Reference:

- The Role of Traditional Rulers in Nigeria Today — The Conversation Africa (https://theconversation.com/traditional-rulers-are-still-relevant-in-nigeria-but-what-they-do-needs-a-rethink-179881)