The Ojude Oba and the Ilorin Durbar may seem like cultural opposites. One sparkles with Yoruba elegance. The other gallops with Northern might. Yet, when viewed side by side, they reveal a surprising intersection of Nigeria’s layered identities.

Two Traditions, One Loyalty

Ojude Oba, meaning “the king’s forecourt,” began in the 19th century in Ijebu Ode. It was a respectful gesture by Muslim converts who, after Eid prayers, visited the Awujale of Ijebuland to reaffirm loyalty. What started as a quiet homage has evolved into a vibrant cultural showcase featuring fashion, music, equestrian displays, and age-grade parades known as regberegbe.

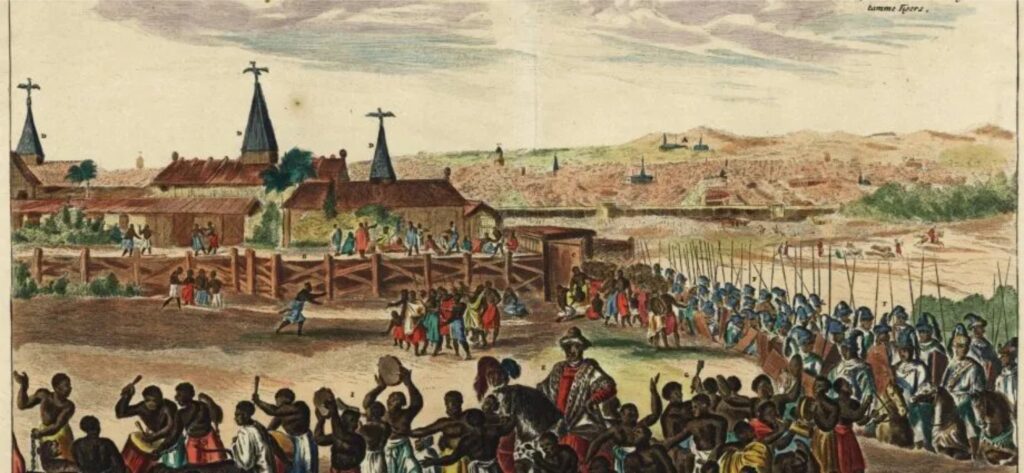

The Ilorin Durbar, though geographically in Yorubaland, reflects a unique blend of Fulani influence and Islamic tradition. Ilorin’s royal structure follows the Emirate system, and the Durbar marks Eid celebrations with displays of cavalry, drummers, sword dancers, and homage to the Emir. Its historical roots reach into the Sokoto Caliphate’s expansion, merging with Yoruba traditions over centuries.

Fashion Meets Firepower

In Ijebu Ode, families wear coordinated outfits, rich in aso-oke, brocade, and lace. They arrive with music, dancers, and pageantry, paying respects to the Awujale. Horses are caparisoned in brightly embroidered fabrics and often guided by young riders from royal houses.

In Ilorin, aristocratic riders take center stage. Their horses wear regalia shaped by Hausa-Fulani tradition. The Emir appears surrounded by warriors and royal guards, riding in with centuries of inherited authority.

Despite the differences in origin, both festivals share key symbols — honor, procession, drums, horses, and an unshaken reverence for traditional rulers.

Ilorin’s Cultural Duality

Ilorin stands at a historical crossroads. Founded by Yoruba, ruled under a Fulani dynasty, and shaped by Islamic law, the city has long embodied cultural duality. The Durbar reflects that. Yoruba drumming sometimes meets Fulani horse formations. Hausa is spoken in palaces, while Yoruba is sung in streets.

This duality doesn’t dilute heritage. It multiplies its meaning. The Emir of Ilorin, like the Awujale of Ijebuland, is a cultural ambassador, bridging the spiritual and the political through ritual and performance.

When Cultures Converge

Though rooted in different ethnic histories, both festivals celebrate loyalty to the crown, the blending of faith and tradition, and the resilience of cultural identity. Tourists, researchers, and descendants from the diaspora travel across oceans just to witness them.

Each year, Ojude Oba and the Ilorin Durbar serve as reminders that Nigeria is not just a collection of tribes. It is a dance of traditions, sometimes contrasting, sometimes overlapping, but always rich.

Not Just Spectacles, But Signatures

These festivals are not performative events. They are cultural declarations. They reaffirm identity. They preserve oral history. They create revenue. They strengthen intergenerational bonds.

And when they happen within weeks of each other, as they often do, they show that unity in diversity is more than a national slogan. It is a lived experience.

—

References